Which Type of Rubric is Best?

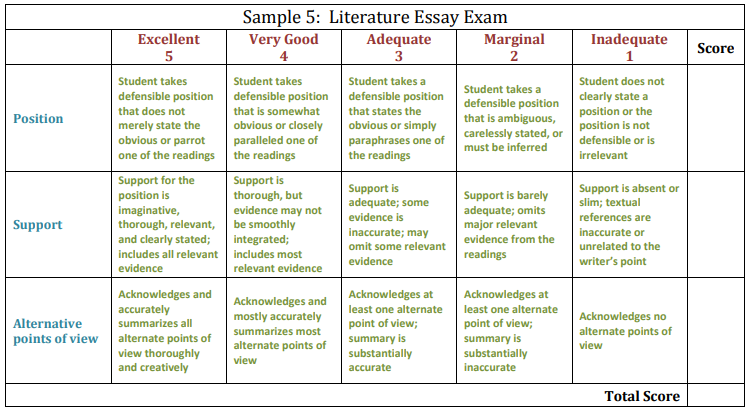

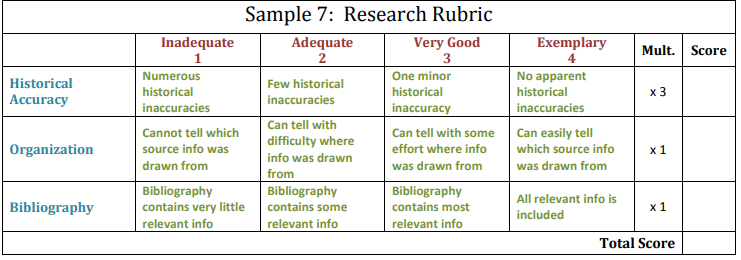

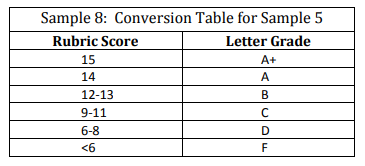

Descriptive rubrics represent the gold standard of rubrics. The descriptors that spell out what is expected of students at each performance level for each criterion make the assessment more reliable so that an instructor can evaluate a group of students’ work more consistently and multiple instructors using the same rubric grade similarly. Without descriptors, it can be difficult to discern the difference between performance level labels such as “excellent” and “very good.” The descriptors also help students to understand exactly what good (or bad) performance looks like at each level and enable instructors to give them more detailed feedback so they can clearly recognize areas of their work that need improvement.

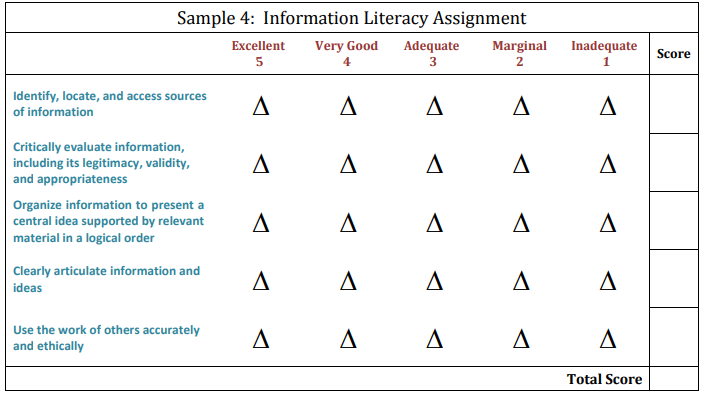

Rating scale rubrics are an alternative to descriptive rubrics for smaller assignments or assessments and when time to evaluate students’ work is scarce. While they provide more sophisticated evaluations of students’ work than do checklist rubrics, rating scale rubrics are not as reliable as descriptive rubrics because their lack of descriptors can make it difficult to differentiate between performance levels. Still, rating scale rubrics are relatively easy to create and use.

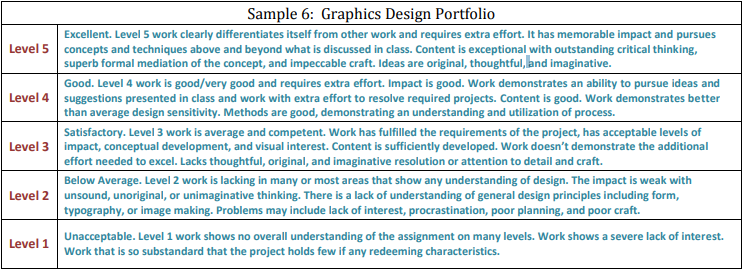

Holistic rubrics may be used when an assessment project is so massive that analytic rubrics would take too much time, such as students’ entrance essays or senior portfolio projects. Holistic rubrics may also be appropriate for minor assignments for which a quick holistic judgment is sufficient. Remember, though, that this type of rubric can prove unreliable if instructors struggle to distinguish between the performance levels.

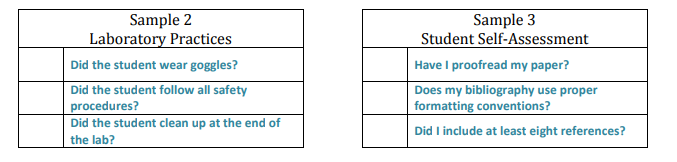

Checklist rubrics are appropriate for simple assessments such as those in which the mere presence of the criteria is what is being evaluated.